Most student pilots, and a lot of experienced pilots, fear stalling an aircraft. During initial training, stalling lessons are given high priority to ensure all students are aware of what an approaching stall looks like, and how to recover with a minimum loss of height if the aircraft does stall.

So what is a stall?

To put it very simply, a stall is caused when an aircraft’s wing exceeds a certain angle (the critical angle of attack) in relation to the airflow (known as ‘relative airflow’).

When this critical angle is exceeded, the airflow on the top of the wing becomes turbulent and a large amount of lift is lost. Most aircraft will lose a considerable amount of height during a stall unless proper recovery technique is initiated. A stall can, under certain conditions, also lead into a spin. A spin is bad news, particularly if you are low to the ground.

To give my students some context (and to reduce their anxiety) I ask them if they have ever planned on hitting a power pole when driving a car? Of course they all say ‘no’. I then advise them that inadvertently stalling an aircraft is like ‘inadvertently’ hitting a power pole. As drivers, we all know that if we stick to the road rules and drive safely in all conditions we mitigate our risk of losing control and hitting a power pole. The same can be said for stalling an aircraft.

Stall avoidance and pre-stall recognition are key

While being trained to recover from a stall is an important part of flight training, I believe stall avoidance is the most important aspect of flight training. Below I have listed some very simple rules that will prevent you from ever stalling an aircraft. If you keep to these rules, your odds of stalling an aircraft are greatly reduced.

- Are you safe? The first rule for all pilots before they go flying is to ensure they pass the minimum personal physical and mental checklist. This personal checklist is to ensure the pilot is not fatigued or stressed or have any physical health issues that could affect the safety of the flight. A common checklist for pilots is known as the IMSAFE checklist you can see in the image below.

- Know your aircraft. All pilots must know the limitations of the aircraft they are flying and this includes power settings, takeoff and approach speeds and stall speeds at all weights and aircraft configurations. If you don’t know the stall speed (limits) then how can you know when you are approaching that limit? This information is all contained in the Pilot Operating Handbook for your aircraft.

- Keep a good outside and inside scan! It is important that the pilot’s eyes are constantly scanning the horizon then quickly back to the primary instruments. This is called ‘the scan’. For visual flying, the pilot’s eyes should be on the physical horizon for most of the time, however, it is important they also keep scanning the instruments. The airspeed indicator is one of the critical instruments that the pilot’s eyes should constantly return to. When students allow their airspeed to get low (for instance on final approach) it’s normally because they are not scanning enough and are just focusing their attention on the runway.

- Trim the aircraft correctly. It’s important the pilot continuously trim the aircraft correctly to avoid excessive pitch forces during critical phases of flight. For instance, if the trim is not correct on take off, this will make it harder for the pilot to maintain the appropriate safe airspeed.

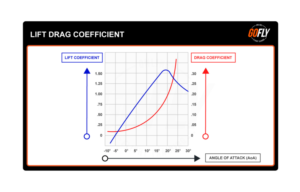

- Angle of attack is everything. An aircraft stalls when it exceeds its critical angle of attack. Put simply, if you never exceed the critical angle of attack then the aircraft will never stall. However, most light aircraft don’t have angle of attack indicators or the pilots may not fly using the angle of attack indicator. For simplicity, all aircraft have published stall speeds. For light aircraft the stall speed is normally based on the maximum takeoff weight and it varies depending on the flap setting. Understanding the relationship between angle of attack, attitude and airspeed is an important part of all pilot’s training. You can also see the relationship with lift and drag that occurs with the angle of attack of the wing on the graph below.

- Attitude and airspeed. During training it is important to ensure the student knows that constantly maintaining a healthy attitude and airspeed (well above the stall speed) will ensure the aircraft will not stall. As an instructor I also look for how quick a student reacts and corrects a diminishing airspeed particularly during take off and landing.

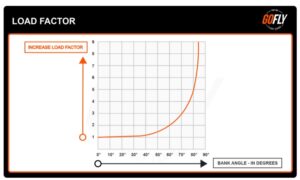

- Understand load factor, weight and balance. Understanding the effect that weight has on the stall speed is critical. A heavy aircraft will stall at a higher speed compared to the same aircraft at a lower weight. It’s also critical to understand that how you load the aircraft (balance) can also affect the stability and stall speed. Load factor is caused by acceleration forces that occur when an aircraft either turns sharply or conducts abrupt maneuvers. When an aircraft is flying level it is experiencing 1G of load factor or one times the force of Gravity. However in a coordinated turn, the forces that maintain the turn increase and this increased force or acceleration is translated into what is known as a ‘G force’. For instance, in a 60 degree angle of bank coordinated turn the aircraft and crew are experiencing 2G or twice their normal body weight. This also has the effect of increasing the stall speed. In this scenario the stall speed is increased by 40%. If the published stall speed is 50 kts in level flight, in a 60 degree steep turn it will now be 70 kts (ouch). All pilots need to understand the effect of G loading on stall speed and never to ‘load the aircraft’ when flying at low speeds or low to the ground. Basically this means to not do any steep turns at low speed and low to the ground. See the load factor graph below, to understand how bank angle affects load factor.

- Allow a healthy buffer above the stall speed. This one is fairly straightforward, unless you are in the final phase of landing, always allow a large buffer above the stall speed when flying. A good rule of thumb is never below 1.3 times the stall speed. However, unless landing or conducting stalls or short field takeoff and landing practice, I suggest to students they should never fly below the aircraft’s best glide speed for added safety.

- Stick to the published operating speed always. If the Pilot Operating Handbook advises that the approach speed is 70 kts at gross weight, then do NOT alter from this speed. They are published in the Pilot Operating Handbook for a reason.

- Stable base and final approach. Ensure you do not overshoot the runway when turning from base to final and if you do, consider conducting a missed approach. Ensure the correct approach speed is maintained on the base to final turn. Ensure that the final approach is stable, meaning a constant rate of descent and safe and constant approach speed and tracking towards the middle of the runway correctly. If you cannot maintain a stable approach then consider conducting a missed approach.

- Retract flaps slowly, in stages and accurately. Depending on aircraft type, raising flaps either after take off or during a missed approach needs to be done carefully, in stages, accurately, and at the correct time. Retracting flaps results in a loss of lift and a pitch change. This could lead to a stall if not done correctly. It is important to ensure that you have a safe flying speed well above the stall before tracting flaps.

- Identifying deteriorating flight envelope. As previously mentioned, an important aspect of training is that the student is able to identify an approaching stall. These warning signs should be hard wired into all pilots. If for instance the approach starts becoming unstable then conducting a missed approach early. Airspeed reducing on final, below the published approach speed, should be noticed and corrected immediately.

- Allowing for weather. It would be insane to conduct a short field landing with a 30 knots gusting wind in a light aircraft. This comes back to knowing your aircraft and your own limitations and once again adding a buffer to add a margin of safety. If the weather conditions are beyond your experience or comfort levels cancel the flight or book an instructor to fly with you.

- Aviate, Aviate, Aviate. All pilots have heard the statement: Aviate, Navigate, Communicate. A lot of stall accidents occur because this simple list of priorities has broken down. During landing and takeoff, the priority should really be Aviate, Aviate, Aviate.

- Be prepared for an emergency and FLY THE PLANE. Conducting an emergency brief to yourself before takeoff will reduce the chances of stalling the aircraft if the worst should occur such as an engine failure after takeoff. For instance, on takeoff a common brief is to tell yourself before take off ‘If the engine fails after takeoff and before [a certain height] I will adopt the best glide and NOT turn back towards the runway.’ This simple brief ensures that you react quickly and make the best decision, should the worst occur.

- Currency. There is no point in knowing all the basic rules of avoiding a stall if you do not fly enough to remain current on your aircraft type. Regular flying and regular dual refresher training is what keeps pilots safe and competent. I recommend all pilots conduct some type of refresher training every six months to work on areas where they are still not feeling confident.

Summary

So, to sum it up, if you want to avoid a stall when flying a plane, do these things:

- Ensure you are mentally and physically fit to fly

- Know your aircraft published speeds in all configurations

- Understand the effect that weight and balance has on stall speed.

- Conduct safety and emergency briefs before take off and landing.

- Maintain a good and continuous horizon to instrument can.

- Stick to the published takeoff and approach speeds

- Do not conduct turns above 30 degrees in circuit or during an approach

- Do not conduct more than a 15 degree turn in a climb

- NEVER allow the airspeed to get below the take off climb speed after take off.

- NEVER allow the airspeed to get below the approach speed until the landing phase (flare).

- Retract flaps slowly (in stages ) above a safe flying speed.

- Continuously trim the aircraft

- Conduct a missed approach if you overshoot the runway

- Conduct a missed approach if the final approach is not a stable approach

- Ensure you are flying regularly and remaining current on your aircraft type.

- Cancel the flight if the weather conditions (wind or visibility) is beyond your experience or comfort level

- Grab an instructor for some refresher training every six months to work on your weaknesses and to improve your flying skills.

Obviously the more training you do the safer and more competent you will become. Slow speed flight and upset recovery training are also excellent ways to increase your confidence and can be conducted safely at high altitude with a competent instructor. Stalls (just like telegraph poles) should never be feared if you have the right training, know the rules, have a disciplined approach to your flying and if you stay current.

To sample all of the videos, theory books, practice exams and blogs on www.GoFly.Online, sign up for the 7-day free trial.